Abstract

The factors influencing charitable donation are complex. The major ones include cultural factors such as traditional historical and cultural values and charitable donation consciousness, as well as external social factors like the economic development level, tax incentive policy, as well as government regulation and social supervision mechanisms. The present chapter is mainly concerned with the cultural and social factors affecting charitable donation.

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, books and news in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.

The factors influencing charitable donation are complex. The major ones include cultural factors such as traditional historical and cultural values and charitable donation consciousness, as well as external social factors like the economic development level, tax incentive policy, as well as government regulation and social supervision mechanisms. The present chapter is mainly concerned with the cultural and social factors affecting charitable donation.

4.1 Cultural Factors

When probing the reasons for the massive difference in the level of charitable donations between China and Western countries, many scholars have emphasized the significant influence of differing traditional cultural values.Footnote1 Generally, the traditional cultural values of a group of people refer to the mainstream core values internalized unconsciously by the group over a complex and lengthy process of historical practice, while the charitable donation awareness of a society reflects the general opinions on charitable donation, which is itself under the deep influence of its traditional cultural values. Despite the subjective nature of cultural awareness shared between them, the former is the cultural conception in a broader and more general and abstract sense, while the latter denotes a more concrete type of behavioral motivation.

4.1.1 Traditional Cultural Factors Influencing Charitable Donation

Cultural tradition and philanthropic cultural concepts exert a significant influence on charitable donation. One way of probing the influence of traditional culture on charitable donation is to clarify the internal mechanism of different cultural traditions and relevant philanthropic cultural concepts influencing charitable donation and related behavior. In Western societies, Christianity makes up the core of traditional culture. By contrast, the core of the traditional culture dominant in Chinese society is Confucian ethics. To explain the gap between China and the West in charitable donation behaviors and levels, we need to look for a cause attributable to cultural differences, so as to get a deeper understanding of the profound influence of traditional culture on the charitable donation mechanism.

The core of the Christian cultural tradition is the concept of “original sin and redemption,” from which the concepts of equality, tithe, and trusteeship were derived. The Christian concept of individual equality means that all are equal before God. Tithing means that individuals should donate one tenth of their wealth or income to the church or relief for poor. According to the Christian idea of trusteeship, the wealth an individual creates in the earthly realm is owed to the favor of God and from the grace given by God to his children, rather than something that belongs to the individual himself. The individual serves as a trustee of God’s wealth and after that wealth reaches a certain level they shall return a part of it to society in return for the grace of God. Even after they pass away, only a small part of their fortune will be left to their offspring as a legacy, while a larger part will be left to society. The Bible’s words that “It is harder for a rich man to enter the temple of heaven than for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle” and the Protestant idea that “It is a shame to die with a great fortune” preached in the Bible have also driven individuals to give their wealth to society. Thus, the Christian cultural tradition not only promotes individual donations through values, but also forms a complete and systematic system of ideas regarding charitable donation that has relatively specific operational norms. At least for Christians, charitable donations are driven not only by self-discipline but also colored by “compulsory” heteronomy.

Traditional Chinese charitable donations values largely rooted in China’s traditional classical culture dominated by Confucianism, that is, thinking of charity as being built with Confucian “benevolence” as the central pillar and including such concepts as people as the root, great harmony, righteousness and interests, filial piety, and fraternal love.Footnote2 Starting by supposing that human nature is fundamentally good, the thought has Confucian benevolence at the core, advocating that individuals, especially “the successful,” engage in benefaction. This is conveyed in the saying, “In times of hardship, one should first treasure oneself; In times of success, one is expected to benefit others.” Thus, the function of benefaction has been defined on this basis as a means of accumulating good deeds for rewards in this world or beyond, which has been described as “doing good and accumulating merit.” At the same time, philanthropy is built on patriarchal kinship relations, so it will increase or decrease in accordance with affinity of blood, ethnicity, and geography.Footnote3

Compared with the influence of traditional Western culture on charitable donation behaviors in the West, the influence of Confucian traditional culture on charitable donation behavior in China is embodied in more selected ways like the purely self-disciplinary orientation, the pattern of differentiation between close and distant relationships, and the familial view of wealth. The “selective rather than common” here refers to the concept of donation by the wealthy which is emphasized by Confucian traditional culture. It requires that successful people with considerable fortune and position fulfill the moral obligation of doing good and accumulating merit, though others do not necessarily have to do likewise. The so called “purely self-disciplinary orientation” means that the mechanism which brings about charitable donation mainly depends on an individual’s internal self-cultivation rather than on external altruistic discipline. In the pattern of differentiation of close and distant relationships, self-help and mutual help are more likely to be encouraged, while donations to strangers outside the pattern tend to be restricted. Differing from the view of wealth underlying the concept of trusteeship in the Christian tradition, Confucian culture stresses the view of familial wealth. An individual makes efforts and gains wealth more for the purpose of bringing glory to his ancestors and passing it on to and benefiting his offspring. Though the foundation in traditional culture and values should not be seen as the deciding factor bearing on charitable donation, the complexity and profundity of such influences still call for much attention.

4.1.2 Charity Awareness Affecting Donation Behaviors

Generally speaking, the awareness of charity concerns the complex of various conceptual forms such as motivation, consciousness, recognition, opinion, and feelings which the members of a society show in their charitable donation. It represents their knowledge, perception, and judgment they have developed regarding charity, as well as the resultant active participation. Analysis of charity awareness can be conducted from the two dimensions of motivation and the structure of awareness.

4.1.2.1 Diversity of Internal Motivation

Regarding the internal mechanism giving rise to charitable donation behaviors, generally speaking, there are two opposing opinions, i.e. rational choice and altruistic choice. When analyzing the awareness of charitable donation, many scholars start from altruistic viewpoints such as compassion and sympathy. However, such explanations simplistically attribute the internal mechanism for charitable donation behaviors to donors’ compassion, ignoring to some extent other possible motivating factors. Economists, when explaining the motivations underlying the phenomena of charitable donations have tended to take “homo economics” as given and thereby regarded the occurrence of charitable donation behaviors as the result of the donors’ rational choice, holding that donation behaviors can bring valuable private objects or realization of personal interests.Footnote4 On the whole, altruistic motivation remains the best theoretical explanation for the occurrence of charitable donation behaviors. After all, it is hardly possible to explain, either logically or practically, the phenomenon of voluntary provision of public goods including charitable goods through only rationality and self-interest.Footnote5

In addition to those based on rational choice and altruism, there are also charitable donation behaviors based on the psychology of mutual benefit and on the concept of trust. Scholars have found it hard to neglect “crowd-following” or “blindly following” behaviors in charitable donation that are caused by pressure from special environments or specific structures. Some scholars are of the opinion that the internal mechanism underlying charitable donation is complex and diversified, and that such complexity and diversity also manifest themselves in that the causes of specific donation behavior are mixed, involving multiple motivations such as a warm glow, social position, and social pressure.Footnote6 The empirical analyses by some Western scholars, such as Moe’s study of the industrial and commercial interest groups in MinnesotaFootnote7 and Mitchell’s investigation of some environmental protection groups also strongly support this view.Footnote8 Both offer in-depth explanations of the mixed motivations of donation behaviors. All these explanations provide theoretical support to the attempt to understand diversified charitable donation behaviors.

4.1.2.2 Hierarchical Awareness Structure

As the structure of charitable donation awareness is hierarchical, it can be divided into five levels. The first level is perception, which refers to the intuitive response to and understanding of charitable donation. The second is the knowledge, the various types of experience and scientific knowledge concerning charitable donation and related issues. The third is the charitable donation values, as well as the motivation for joining actively in charitable donation activities. The fourth is evaluation, which is concerned with charitable donation and related issues. The fifth is behavioral intention, referring to donors’ conscious orientation of motivating themselves to take part in charitable donation activities. We can simplify these five levels into three: the elementary level of awareness, which is the stage of obtaining knowledge of charitable donation behaviors, covering the aforementioned levels of perception and knowledge; the middle level, that is, the stage of approving and accepting charitable donation behaviors, covering the aforementioned levels of attitude and evaluation; and the advanced level, a stage of endorsing, believing, and advocating for charitable donation behaviors, i.e. the aforementioned level of intention (see Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Levels of awareness structure

Full size table

Lower levels of charitable awareness are limited to only basic knowledge of charity concepts and an individual with such awareness does not have a strong willingness to make charitable donations. Before charitable donation is understood as a citizen’s responsibility and obligation, the behaviors of not donating or passively participating in donation are indicative of lower charity awareness. In fact, a sense of responsibility is at the core of charity awareness and, compared with other social responsibilities, charity responsibility is on the higher level. Just as different people reach different realms of morality, the charity responsibility embodied in different members of the society also differs across a gradient.Footnote9 An advanced level of charitable awareness refers to an individual gratefully seeing the relationship between himself and the society where he belongs and, aware of his social responsibility, thus repaying society directly and initiatively in a charitable way. Such realm of knowledge represents an advanced level of charity awareness that a society advocates and fosters.

4.1.3 China’s Current Charity Awareness

Having entered the twenty-first century, China has witnessed the rapid growth in the total volume of charitable donations. From 2000 to 2012, the annual chained rate of increase for social donations was about 53.9%,Footnote10 and the chained relative increase rate in the special years of 2003 (the SARS epidemic) and 2008 (the catastrophic Wenchuan earthquake) respectively reached 115 and 260%. These changes reflect the enhancement of charity awareness in contemporary China, but cannot cover up the extant lagging behind and passivity, as well as the low degree of development.

The lag in charity awareness is indicated by the following two facts. On the one hand, the overall level of the charitable donation awareness in China lags far behind the overall level of China’s economic and social development, with a very obvious cultural lag behind the rapidly developing economy and the overall development level of Chinese society. On the other hand, Chinese charitable donation awareness shows passivity and lags behind the development of the charitable donation level of the country. Here the “passivity” refers to, as far as why it occurs, too much dependence on top-down government pushes, featuring weak bottom-up endogenous development.

The frequent occurrence of mandatory and passive donation behaviors is typically indicative of the passive features characteristic of charitable donation awareness in China. For example, in the “One Day Charity” activities, certain sums are automatically deducted from the salaries of the civil servants and employees of government agencies and public institutions, while at the same time instances of “compelled donations” and “extorted donations” have continued to occur. Although such phenomena of “being forced to donate” contribute to lifting the absolute total of charitable donation, they are detrimental to the cultivation of charitable donation awareness and, to an extent, restrain the normal development of charitable donation awareness on the part of Chinese citizens.

Compared with developed countries in Europe and America, development of charitable donation awareness in China is, on the whole, still at a low level. As concluded by a survey in 2003 of Chinese citizens’ charitable donation awareness, “There has not developed self-conscious and strong charity awareness in the whole society.”Footnote11 According to a similar survey conducted in 2012, “In China, there are still groups of the people whose charitable donation awareness is yet to be enhanced.”Footnote12

4.1.4 Main Paths of Elevating Charity Awareness

The influence of public policies on charitable donation awareness tends to be through direct standardization and guidance, while having strong operability. The influence of modern media and public opinion on the general public’s awareness of charitable donation should not be ignored either. Thus, this section will probe the main paths of elevating charity donation awareness from the two angles of social policies and cultural advocacy.

4.1.4.1 The Path of Public Policy

The policy-based approach to elevating China’s charity donation awareness is to eliminate obstacles hindering organizations and individuals from entering the charitable domain, strengthen process supervision, and improve the incentive mechanism, primarily by introducing public policies. First, more effort should be made to remove barriers in registration and management of social organizations, so as to expand the applicable scope for organizations and to broadly implement the policy of allowing social organizations to apply to register directly with civil affairs departments. Thus, the general public’s enthusiasm to engage in charity can be greatly invigorated, promoting their actively taking part in charitable donation. Second, administrative dominance should be further mitigated and, by adjusting relevant policies, officially run NPOs should be gradually turned into charity organizations enjoying relatively high levels of independence, changing the monopoly position of officially-run NPOs in the charity market. Thus, the efficiency of allocating charitable donation resources can be bettered and the strength of non-governmental charity organizations can be boosted. Thirdly, process supervision should be further intensified and the credibility of charity organizations should be elevated by setting up mechanisms for assessment, ensuring openness and transparency, and elimination and exit suitable to the actual development level of the China’s charity donation undertakings. Such measures help remove the public’s various misgivings over charity organizations, gradually fortify the public’s confidence in charitable donation, and stimulate their internal vigor to donate. Finally, the policy-based incentive mechanism applicable to different subjects when donating should be improved. By adjusting the tax law, the preferential taxation policies oriented toward enterprises as donors should be improved and implemented more effectively, the tax deduction rate for individual donations should be increased in a reasonable manner, and the conditions required to apply for the tax deduction should be simplified. These policy-based means can be used to guarantee the effect of economic incentive mechanisms and to satisfy the needs of various donation subjects to make rational choices in return for benefits.

4.1.4.2 The Path of Cultural Advocacy

The path of cultural advocacy refers to the method of exerting a subtle influence on the public and enhancing their modern charity awareness by means of the developed mechanism of modern communication.

Firstly, following philanthropy objectively. The “objectively” here means that when stating and commenting on a charity event, the media should rationally assess the significance of charity and its future prospects, reducing as much as possible the negative influence of subjective factors like radical views and suppositions, and understand those unavoidable problems of charity’s initial development stage, avoiding as much as possible fragmented and isolated news or such ways of reporting.

Second, giving full play to the positive function of the media to construct a healthy social and cultural atmosphere for nourishing charity awareness. The influence of news media on charity donation awareness can be realized by constructing values and concepts. Both core values of the society like integrity and friendliness, which are closely related to charity, or views of wealth and the rule of law, which are closely related to charitable donation behaviors, can be shaped and solidified by the public opinion promotion in the news media.

Lastly, enhancing the public’s capability to distinguish between true and false charity information. Events in recent years, such as Meimei Guo flaunting wealth and Suntech’s “charity fraud” caused more and more people to question charity organizations. Though some of the incidents are not made up by the media, there is a considerable amount of exaggerated information based on hearsay evidence. In this era of “We Media,”Footnote13 when a public event occurs, the media should, as much as possible, avoid false information and misleading the public. Charitable organizations themselves should adhere to a just and transparent operation mechanism and respond as soon as possible once any critical incident occurs, turning the “crisis” into an opportunity. By nurturing their own credibility, they can bolster the enhancement of social charity awareness.

4.2 Economic Factors

4.2.1 Economic Level and Charitable Donation

The influence of the economic level on charitable donations can be summarized as follows. Under different economic conditions, the available quantity of charity resources and development levels of different charity organizations both differ and the interactive combination of these two factors brings about differing levels of charitable donations. The main influence of China’s imbalanced regional donation on charitable donation is embodied in the charity donation level descending a “staircase” from the east through the middle and descending all the way to the west. As shown by the annual ranking of Chinese donors, the east, China’s most economically developed region, exceeds central and western China in donation volume, the atmosphere for social charities, entrepreneurs’ participation in public welfare, and the maturity of the public welfare and charity organizations.

4.2.1.1 Differences in Distribution of Charitable Resources

The economic level is an important factor determining the availability of charity resources. Generally, charitable resources are relatively abundant in developed regions and are capable of providing sufficient force for charitable donations. By contrast, charitable resources are relatively lacking in less developed regions and the donation capacity is correspondingly lower.

The marked difference in the distribution of charity resources is signified by the imbalanced regional distribution of both enterprises and industrial scale. Of the 63,314 large and medium sized industrial enterprises covered by the statistics issued by PRC National Bureau of Statistics in 2012, the 39,681 enterprises in the eastern China had business income equal to 62.9% of the national total, while the corresponding industrial enterprises of central and Western China accounted for 22.2% and 14.9% respectively of the total.Footnote14 According to data from the Forbes China Charity Rank, for the year 2014 the top ten corporate donors were all located in Beijing Municipality, Guangdong Province, Fujian Province, and some other eastern provinces (see Table 4.2). Corporations on the list from Henan, Shanxi, Sichuan and some other central and western provinces were all low in either donation volume or number of donations made.

Table 4.2 Provinces and regions where the top ten corporations on Forbes 2014 List of China’s Charity are located

Full size table

In some provinces where private economy is developed such as Zhejiang, private companies have already begun to play a main role in charitable donation. As shown data from the “2012 Report of Charitable Donations in China,” the amount given in 2012 by private companies reached 27.506 billion yuan, accounting for 57.98% of all enterprise donations. Since 2007, when nationwide donation statistics began to be released annually in China, the amount donated by private companies has been over half of the total given by enterprises. As the private economy in central and western China is clearly behind, charitable donations by the private enterprises in these two regions have not been the main source of income for charitable organizations located there.

4.2.1.2 Uneven Maturity of Charitable Organizations

The maturity of a charity organization as a major recipient of donations depends on the specific level of economic development. A charitable organization’s credibility and capability to integrate charitable resources clearly affects the volume of charitable donations it receives.

The growth of NPOs across the country is regionally imbalanced as result of imbalanced development between different regions. Whether in absolute number or capabilities, local NPOs are strongest in more developed eastern provinces, especially Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shanghai, and Guangdong. The volume of funds raised by charity organizations in eastern provinces is clearly higher than in the central and the western provinces and an overwhelming majority of the charitable funds collected countrywide by charitable organization comes from eastern provinces.Footnote15 As the leading city in China’s Yangtze River Delta economic area, Shanghai has seen its philanthropy flourish. In 2013, the Shanghai Charity Foundation took in RMB 707 million in income from its programs to raise donations, far exceeding the capacity of other national public foundations. Excluding the Tibet Autonomous Region Charity Federation, in 2011 China’s 31 provincial charity federations, raised RMB 4.67 billion, of which 47% came from charity federations of the eastern provinces and only 28 and 25% from those of the central and western provinces respectively.Footnote16

Most of the funds raised nationwide are spent in the eastern provinces. In 2010, the statistics of thirty provincial charity federations shows that they spent a total of RMB 6.3 billion on charity, of which those in eastern provinces spent RMB 3.39 billion, accounting for 53.71% of the total (see Table 4.3).Footnote17

Table 4.3 Expenditure shares of three regions of China in 2010 among 30 provincial charity federations

Full size table

4.2.1.3 Regional Differences in Total Charitable Donation Volume

In philanthropy the economic level of a region can directly be seen through the level of charitable donations. Differences in regional economic development cause the uneven distribution of charitable donation resources, with total donation volumes in economically developed regions outweighing those of less developed regions.

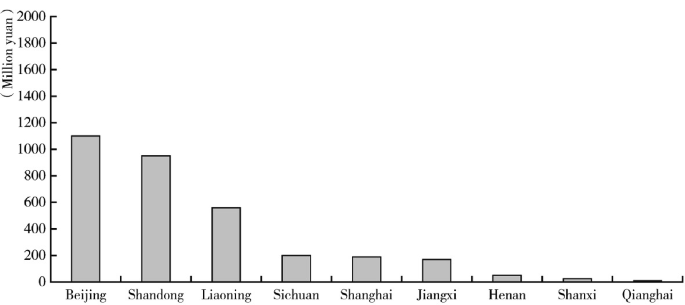

Analyzing samples of domestic data on donationsFootnote18 shows that in 2011 the three provinces of Guangdong, Beijing, and Fujian had the highest level of donations, with each over RMB 2 billion. The total volumes of donated funds and materials in Shanghai, Shandong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu were all over RMB 1 billion. By contrast, some provinces in central and western regions such as Jiangxi and Xinjiang donated less than RMB 100 million.Footnote19 Additionally, according to data on social donations received directly by the civil affairs departments of the various provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in 2013, the total donation volumes differed markedly by region. The amount directly received by the civil affairs departments of Guangdong alone reached as high as RMB 1.82 billion and those of Beijing and Shandong reached RMB 1 billion yuan, while those of Shaanxi and Qinghai received only a few million (see Fig. 4.1).Footnote20

Fig. 4.1

Source CPR Ministry of Civil Affairs (2013)

Total amounts directly received by civil affairs departments in ten provinces in 2013.

Full size image

4.2.1.4 Influence of Individual Economic Strength on Donations

An individual’s economic strength has particularly clear influence on their donation behavior and personal incomes level directly affects an individual donor’s capability to donate. Both the results of a survey jointly published in 2008 by the Shanghai Charity Foundation and Fudan University School of Social Development and Public Policy and also the data on Chinese citizens’ public welfare behavior that the Beijing Normal University School of Social Development and Public Policy obtained by surveying 27 Chinese cities in 2011, show the significant influence of an individual’s economic level on their donating behavior.

(1)

Weak personal economic capability is the main reason for not donating. A significant number of Shanghai citizens who had not donated in the two years prior said that their weak economic capabilities were the key reason for their donation behaviors. They made up 34.3% of all respondentsFootnote21

(2)

Significant positive correlation exists between an individual’s social and economic position and their charity donation behavior. Individual charitable donation behavior is subject to the influence of one’s own personal economic status. As their overall level of wealth rises, individuals will be more willing to participate in charitable donation activities. In the aforementioned Shanghai survey, more than 90% of respondents said that if their income increased, they would give more to charity (see Table 4.4). Based on a Tobit model of the survey data from Beijing University on Chinese citizen’s public welfare behavior, personal work income increased by 1%, and average donations increased by 0.25%.

Table 4.4 Statistics on relationship between citizens’ economic strength and their willingness to donate

Full size table

An individual’s income has a direct bearing on their donation amount, number of donations, and willingness to donate, while an enterprise’s donation level is subject to its stage of growth. Generally, an enterprise will experience three stages: the primitive accumulation stage, the stage when it pursues scale and expansion, and the stage when it strives to build itself as a corporate citizen.Footnote22 Most Chinese enterprises are still in the first two stages, that is, they are rising. In the primitive accumulation and expansion stages, enterprises worry about social donation increasing risk. When they stand on a firm economic basis they will strive to fulfill more of their social responsibility as corporate citizens and to engage in charity.

4.2.2 Impetus and Influence of the Economic Benefit Factor

There is an obvious positive correlation between charitable donation and the level of economic development. However, other economic factors that promote charitable donation should also be considered. An important one is the return in benefits brought about from charitable donation. This factor serves as the internal drive behind charitable donation behavior and the public’s awareness of participation.

4.2.2.1 Economic Benefits of Charity Organizations

Charity organizations are NPOs, but this does not mean that they cannot or should not obtain economic benefits from their operations. The launching and founding of many charity organizations, particularly most of the non-governmental or non-enterprise units, are naturally driven by certain future benefits. The sponsors or investors, though they cannot earn handsome profits, can obtain a relatively fixed income for the sustained development of their organizations. For example, the main areas into which a charitable foundation invests its capital include industrial entities, stocks, bonds, and insurance. Differing from an enterprise, which seeks economic interests and benefits so as to enlarge its market share, a charity organization sets greater store in the relevance of its economic benefits for the public welfare. Charity organizations’ participation in raising charitable funds and operating those funds is conducive to maintaining and increasing the value of their assets and, more than that, can effectively boost their independence and ability to offer services thus better fulfilling their positive function in serving public welfare. A charity organization which has a scientific system for operating its assets and has fostered high social credibility is a favorable factor for stimulating various social forces to participate in charitable donation.

4.2.2.2 Enterprise Benefits

Under a market economy, enterprises tend to treat charitable donation as an important means of competition. An enterprise needs to take into consideration both economic benefit and social responsibility, for, its existence depends just as much on social responsibility as it does on economic benefit. Social donation signifies tremendous social value for an enterprise, as it enhances its social image and is “the only way it must pass to ensure its sustainable operation”.Footnote23 First, social donation is, to a considerable extent, conducive to an enterprise bettering the management efficiency of its leaders, as well as enhancing employee cohesion and internal management. Second, through social donation, an enterprise can display its sense of social responsibility, which helps it win positive appraisals and trust from all sides and thus tighten its affinity with the relevant governmental departments and with all sectors of society. A scholar pointed out that, “As far as a transnational company in China is concerned, by providing various public welfare donations and supporting China’s education, it can give a favorable impression to the government and win its trust, and thus enter into sound cooperative relationship with the governmental departments, which should be a preferable path to participating indirectly in politics.”Footnote24 Last, an enterprise making strategic donations can better its environment and add to its competitive advantage. When an enterprise invests strategically to those mutually beneficial areas of charity which can bring about both social and economic benefits, it can increase its sales income and thus have success in both public welfare and its own performance.

To an enterprise, proper participation in public welfare donation can be a special marketing tool described as “Cause-Related Marketing.” This refers to the type of corporate charity activity by which an enterprise can fortify its own capability to make money. This type of corporate charity activity can be combined with specific marketing activities or be organized jointly by an enterprise and an NPO, particularly a charity organization.Footnote25 In this way, if an enterprise, by choosing a public welfare area favorable to the sales of its products, makes donations and also calls for others to donate, it will ultimately expand its market influence and increase its profits. As a new marketing tool, Cause-Related Marketing has become increasingly popular among enterprises, as it considers benefits for enterprises, consumers, and society, and thus wins extensive support from all sectors of society.

4.2.2.3 Individual Benefits

According to social exchange theory, charitable donation can directly or indirectly bring benefits that include internal and external rewards to the donor. The “internal reward” refers to the direct return, like love, gratitude, satisfaction of interests, or sense of honor from a social exchange relationship that a donor establishes in the process of donating. The “external reward” refers to a return from elsewhere, which generally means the realization of relatively long-range objectives in future, such as gaining status, obtaining assistance, or being obeyed.

Additionally, an individual’s motivation to donate can also be avoiding taxes. For example, as the rate of inheritance tax in Western countries is progressive on the basis of a surtax system (the highest rate can be about 50%), many rich people are liable to give their fortune to charity. Since China has not begun to levy inheritance taxes and gift taxes, it has not established an “anti-driving” mechanism in which the inheritance tax and gift tax can restrict the transfer of fortunes and thus promote charitable donation. Due to the absence of these types of taxes, many people of the high-income class prefer to leave their fortunes to their relatives rather than give them to social charitable undertakings.

4.2.3 Paths for Promoting the Benefit Feedback for the Development of Charitable Donations

Paralleling the great efforts which have been made to increase incomes, the tax system and other supporting measures need to be improved to protect donors’ appropriate benefits, so that charitable donation behaviors can be durably and effectively stimulated, thus promoting the sound growth of philanthropy.

As far as a charity organization is concerned, it needs to start by ensuring the basic operations of its funds and then seek a breakthrough in accessing secure investments. Firstly, the public financial support from the government is an indispensable economic resource for a charity organization. Take developed countries and regions as an example. The social donations available to a charity organization, though an important income source, do not make up the only source, as a considerable part of its funds comes from government financial investment.Footnote26 An example is Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, which allocates funds for local non-governmental charity services and undertakings, objectively guaranteeing charities serving as an important pillar supporting the social security system. Thus, the charity domains and levels to be supported by government finance and the channels for that purpose should be clarified, and by formulating proper policies, institutional financial support should be provided for charitable organizations, reducing the funding pressure on them in their long term development process. Secondly, with regard to maintaining and increasing the value of their assets, charity organizations should be, getting past the restraints from their public welfare status and under the precondition of ensuring the security of their funds, encouraged and guided to maintain and increase the value of their assets by means of the various ways available in the money market. At the same time, the demarcation line between the operable capital and the donation income of charitable organizations should be made clear and the accounting of their financial affairs and their tax treatments should be handled differently.

As far as enterprises are concerned, maintaining fair competition in charitable donation, with different systems of enterprise ownership on an equal footing, is also an important means of promoting corporate donations. Currently, the evaluation of corporate donation behaviors is based more on the absolute amount than on the relative donation capacities or donation ratios of different types of enterprises. This is unfair to a large number of private enterprises which are not state-run monopoly enterprises, yet which take active part in philanthropy. Therefore, the future system of social evaluation which will guide enterprises as donors should fully respect enterprises’ own economic strength, emphasize their autonomy in carrying out strategic donations, and offer suitable preferential policies to them as a stimulus, thus creating a sound environment where, as donors, they can engage in benign competition.

As the web and electronics technology develop rapidly, many forms of new media have become easily accessible. This has brought about more convenient channels for charitable donors to obtain reputational feedback. Charity organizations can, by designing and operating a series of information platforms, satisfy the emotional and moral needs of individuals’ donation behaviors. Thus, after individuals make donations, the immediate and effective spreading of the information is beneficial both to affirming the value of the individual donation behavior, so as to give feedback to the individual donors, but also to have them serve as a model for others.

4.3 Tax Factor

The impact of taxes on charitable donation is mainly reflected in the implementation of the preferential policies for charitable donation through relevant laws and regulations of the tax law and tax departments, thus stimulating enterprises, individuals, and other organizations to actively participate in social charitable and donation undertaking.

4.3.1 Influence of Taxation on Enterprise Donation

The most direct and explicit return brought about by charitable donation is a reduction in taxes. When an enterprise reduces its amount of tax payment by making donations, it is actually a tax transfer made by the government. If an enterprise put a part of its profits into social public welfare undertakings, it decreases the government’s operations among the intermediate links, greatly increases the funds available to the charitable undertakings, and indirectly lifts its corporate performance, and thus is conducive to overall social and economic development. In China, the current basic income tax rate is 25% for enterprises, 20% for those small and low-profit enterprises and some overseas enterprises, and 15% for new hi-tech enterprises.Footnote27 Different types of enterprises may, according to different preferential taxation policies, choose themselves different recipients and donation channels. Enterprises with low annual taxable income can fully use the different rates of preferential taxation and readjust their charitable donations in order to reduce their tax burden and maximize their benefits. As for large enterprises, since tax policies for public welfare donations are closely related with their total final profits, they have to consider fully the interests of all shareholders (particularly medium and small shareholders) before making donations and attempt to design suitable donation schemes which maximize the efficiency of their donations and at the same time avoid hurting the interests of their shareholders.

Of the current categories of tax in China, the two which significantly influence corporate donations are the value-added tax (a tax on turnover) and the corporate income tax (an income tax). The influence of value-added tax on the donation activities of an enterprise affects, generally speaking, its non-cash donations, for when its products have not entered into the market the tax burden is fully shouldered by the company itself. As stipulated in the Interim Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Value-Added Tax, when an enterprise turns over the goods produced by itself, made through consigned processing, or purchased, as gratis gifts to others, they should be regarded as sales, subject to financial accounting, and according to the composite assessable price computed on the basis of the average prices at which the taxpayer or other taxpayers in a recent period sell the same type of goods, the sales volume shall be decided and the corresponding value-added tax shall be paid according to law.Footnote28 Therefore, donating behaviors will incur payment of value-added tax to a real extent. According to the current stipulations on the value-added tax, when donating something, an enterprise may choose different materials for donation so as to minimize its corporate tax burden. This is the main influence of value-added tax on its donation behaviors.Footnote29 As for the enterprise income tax, it divides the ways in which an enterprise makes public welfare donations into different categories, each enjoying a different preferential policy (see Table 4.5). The latest enterprise income tax in China cancels the provisions for the full tax deductions being applied to public welfare donations given by enterprises via NPOs to some areas such as the Red Cross Society and public benefit sites designated for teenagers’ activities, as well as donations by foreign enterprises. However the full tax deduction is still applicable to special public welfare donations for disasters and important incidents. Instead, according to the new provisions, the donated amount can be deducted to an extent not exceeding 12% of total profits. It is also stipulated that anything below the quota of public welfare donations which are not deducted and the amount donated above the quota of the fiscal year cannot be carried over to the next year. This will promote an enterprise, when choosing specific means of donation and quotas, to fully consider how to maximize its benefits.

Table 4.5 Provisions in current laws and regulations for preferential taxation of enterprise charitable donations

Full size table

4.3.1.1 Positive Influence

The current laws and regulations provide clear provisions for the preferential taxation of the donations made by enterprises at home and abroad. Among them, the “Law of the Peoples Republic of China on Donation for Public Welfare Undertakings” (1999) stipulates that the public welfare donations made by companies and other enterprises according to law enjoy preferential income taxation; the import duties of materials donated from outside the borders to Chinese public welfare undertakings and the value-added tax from the import process can be reduced or exempted.Footnote30 According to the revisions made in 2007 to the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Enterprise Income Tax,” the percentage of pre-tax deduction on donations rose from 3 to 12%, the base for tax exemption changed from the previous total taxable amount to the yearly total profit, and the amount of donation for preferential tax deduction was made uniform for both Chinese funded enterprises and foreign funded enterprises. All these changes indicate that the Chinese government is supporting strongly corporate donation behaviors through introducing more favorable tax exemption policies.

Additionally, more and more public welfare organizations have been qualified for pre-tax deductions for donations. In 2008, there were 66 social organizations for public welfare registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs and entitled to the qualification for pre-tax deductions for public welfare donations, while by 2012 there were 148. 2013 saw 170 social organizations for public welfare qualified in two groups successively by Ministry of Finance, State Administration of Taxation, and Ministry of Civil Affairs for pre-tax deductions for public welfare donations. This increase is conducive to gradually expanding the channels for social donations, lowering the threshold for enterprises to make public welfare donations, and enlarging their range of possible means of donation to choose from.

4.3.1.2 Problems

The effect of the tax incentive mechanism depends on whether the tax system is designed scientifically and reasonably and also whether it is put fully into practice. Currently, there are still some problems preventing the tax system from playing its incentive role that involve both inadequate demand for preferential tax policies and institutional obstacles.

Tuan Yang and Daoshun Ge’s survey finds that many enterprises are not very eager to obtain tax exemptions on donations. The main reasons lie in that the donated amounts are low, the procedure of applying for deductions is complicated, and the tax deduction involving donated materials is not easy to handle, among others. Besides, as the tax deduction is a behavior that comes after the donation behavior, the possible transaction cost determines whether it is worthwhile to apply for that deduction, and, what is more, since a great many donations made by enterprises are disbursed from their costs, welfare expenses, non-business expenditures, and administrative operating expenses, they do not need to apply for tax deductions.Footnote31

The reasons why Chinese funded companies seldom consider applying for tax exemption are as follows. Firstly, they have not been fully informed of the policies on the pre-tax deduction of donations. Secondly, their donations are disbursed in the cost expenses. Thirdly, it is difficult to apply for an exemption for donated materials and donations by employees. Foreign funded companies, though more familiar with the relevant policies of tax deduction and exemption, have found it challenging to handle their applications. There are two main reasons for this situation. First, it is hard for them to get proof for the tax exemption. To get the proof, they must have their donations to go to designated charity organizations. As foreign funded companies have relatively more programs of their own for mutually beneficial donations, they do not necessarily donate via a designated charity agency and thus have trouble obtaining the relevant proof. Second, as foreign funded companies in China have enjoyed a preferential tax deduction for many years, applying for tax deductions or exemptions for low-volume donations, donated materials, and donations by employees is relatively unimportant.Footnote32

Currently, the main obstacles enterprises are faced with in realizing the tax deduction and exemption of their public welfare donations are as follows. Firstly, judging from the results of tax incentive policies, the current preferential taxation of charitable donations has produced different effects on enterprises with different systems of ownership. As the administrative mechanism plays a dominant role in the management of SOEs, the tax deduction and exemption policies exert little influence on them. For the private enterprises, the situations in different regions are quite different. In some regions, the local taxation departments decide on a fixed rate for taxable income on the basis of enterprise income, from which the tax can be computed directly. Thus, the charitable donation level has little to do with the corporate taxation. Secondly, regarding the donation channels, as it is stipulated by law that direct donations to recipients do not enjoy tax deduction and exemption, and, in fact, many enterprises give donations directly or via social organizations for public welfare. Many of these recipients are not qualified for tax deduction and exemption or to issue tax exemption invoices, so the influence of the tax deduction and exemption policies is very limited for these enterprises. Thirdly, looking at donated assets, many Chinese companies give non-cash donations, and, in addition to non-cash donations such as materials and services, the number of equity donations has been growing rapidly. As provided for in “Circular on Financing Issues of Enterprise Equity Donations for Public Welfare” issued by Ministry of Finance in 2009, natural persons, legal persons that are not state-owned enterprises, and other enterprises held by economic organizations as investors can make equity donations, while SOEs cannot allowed to do so. At present, as the practice of the tax deduction and exemption on equity donations is still in a pilot stage and, what is more, the current taxation system is not clear on the pricing standard for non-cash donations. These all affect the role played by tax incentives.

4.3.2 Influence of Taxation on Individual Donors

4.3.2.1 Individual Donation Tax Policies

Regarding measures for preferential taxation on individual charitable donations, the current “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Donation for Public Welfare Undertakings” (1999) expressly stipulates that “When donating property for public welfare undertakings according to the provisions of this law, natural persons, individual businesses of industry and commerce may be given preferential treatment in individual income tax according to the provisions of laws and administrative regulations.”Footnote33 Though the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Individual Income Tax” has been revised for five times in the period from 1999 to 2011, the sections concerning provisions for preferential taxation of charitable donations have remained substantially the same. It is stipulated that “The part of individual income donated to educational and other public welfare undertakings, shall be deducted from the taxable income in accordance with the relevant regulations formulated by the State Council.”Footnote34 The “Regulations for the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Individual Income Tax” (2011) specifically stipulate that “The donation by individuals of their income to educational and other public welfare undertakings, and to areas suffering from serious natural disasters or poverty, through social organizations or government agencies in the People’s Republic of China. That part of the amount of donations which does not exceed 30 percent of the amount of taxable income declared by the taxpayer may be deducted from his amount of taxable income.”Footnote35 At the same time, tax incentives oriented towards taxpayers’ charitable donations also involve such preferential taxation such as on properties and behaviors. At present, China has not introduced any policy of preferential taxation on commodities, due to the limitation of inadequate identification of donation behaviors among the circulating links and also to prevent some taxpayers from going into profit-seeking activities in the name of charitable donation.

4.3.2.2 Weakness of the Present Tax Incentive Policies for Individual Donations

Currently, there are some illogical parts of the design of the taxation system for individual donations. If an individual donor fails to choose the proper mode and channel of donation, it is possible that, after giving a donation, he has to make a supplementary payment of the income tax. This may cause another result, that is, rather than donating to a public welfare organization, a donor may donate directly to the donee or not donate at all. However, in the actual process of donation, a great number of individuals do not know much about the policies and articles concerning donation, resulting in them receiving less than the benefits they deserve or even unknowingly violations of law. In 2005, the civil affairs system received a total of 1.7 billion yuan individual donations nationwide, yet the individual tax refund rate was zero.Footnote36 Compared with the developed countries and regions, China’s donation policy is singular and flawed. The incentive function of tax policy is inadequate, which is embodied in the following aspects.

Firstly, it is difficult to get the proof required to apply for individual tax relief. The conditions for enjoying tax deduction and exemption are relatively rigorous and only by donating to public welfare organizations identified by governmental agencies as qualified for pre-tax deduction on public welfare donations can an individual take advantage of the tax refund policy. Currently, only a small number of officially run public welfare organizations such as China Charity Federation, Project Hope Foundation, and the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation have the authority to issue the proof required for qualification to apply for tax deduction and exemption, while regular donations in large quantities to community-based charity or service organizations cannot obtain such proof. This is disadvantageous to encouraging social donations. When individual citizens make direct donations to the receiving units or individual recipients, they cannot get pre-tax deduction of income tax.

After a work unit or an enterprise organizes its employees to make individual donations, usually it can only be offered a uniform donation certificate, while individual donors cannot get their own donation receipts. As for the civil servants in government departments, since their income taxes are withheld and remitted by the financial agencies, they have to go through a complicated process involving transferring documents and handling the tax deduction formalities if after their donating behaviors they need to apply for tax deduction or exemption. Additionally, in the case of a man and his wife donating their common property, questions such as how to divide the deducted amount and how to separate their donation receipt need further study.Footnote37

Secondly, the procedure of refunding donation tax is complicated. China’s current procedures for handling individual donation tax deduction and exemption are very complicated. When some enterprises apply for handling the tax exemption formalities after their making donations, they even have to resort to use of guanxi. An overwhelming majority of employees have participated in various material or cash donation activities organized by their communities or work units, but almost none of them have attempted to apply to the taxation departments for any income tax exemption. A senior official in charge of donation and relief work in a government agency once donated 500 yuan purposely and it took him two months to go through ten steps before he got a 50 yuan tax exemption.Footnote38 This case exposes the tedious tax refund process. Many taxation agencies do not even set up a standard procedure for handling the tax refund affairs.

Thirdly, there lacks a mechanism for an “anti-driving” effect. As the inheritance tax and gift tax restrict the transfer of property, they can produce the effect of anti-driving donations. However, China has not introduced these two taxes, which has pushed, to some extent, people to accumulate wealth or pass it on to their offspring rather than donate it to society or charity organizations. As shown by experience, the inheritance tax and gift tax exert considerable impact on donations. The inheritance tax belongs to the category of property taxes and the object of taxation is the net value of the property left by the deceased owner. At present, more than a hundred countries levy an inheritance tax. Collecting this tax will supplement and improve the state’s tax sources, and also be beneficial to adjusting the societal wealth gap. The gift tax levied on property gifted by its owner to others before their death is a subsidiary tax to the inheritance tax, aiming at preventing the property owner from transferring his property when alive in order to have the inheritance tax on property after his death reduced.

4.3.3 Influence of Taxation on the Income of NPOs as Recipients of Donations

4.3.3.1 Preferential Taxation Factors Promoting NPOs as Receivers of Donations

1.

Guarantee and promotion on the legal level

The provisions for preferential taxation of the donation income of charity organizations are found in the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of Foundations” (2004), the “Interim Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Value Added Tax” (2009), the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Customs” (2013), and documents issued by the PRC Ministry of Finance and State Administration of Taxation such as the “Circular on Issues of Identification and Administration of NPO Status for Tax Exemption.” Some of them stipulate that the donation income of NPOs (including charity organizations) meet the favorable conditions required for tax exemption. The incentive for materials charitable organizations receive from overseas donors is mainly provided by preferential import value-added taxation and preferential tariff treatment. For example, import duties and the value added tax on the import chain are exempted for materials directly donated gratis for poverty assistance or charity by overseas donors to the following six social organizations: the Red Cross Society of China, National Women’s Federation, China Disabled Persons Federation, China Charity Federation, China Primary Health and Care Foundation, and Song Qingling Foundation.Footnote39

2.

Regulations and rules closely linked with relevant tax laws

Existing rules and regulations are continuously updated and old ones are replaced in a timely manner. For example, regarding the regulations on the recognition and administration of NPOs’ qualification for tax exemption, in recent years, the regional limitation on NOPs’ public welfare activities has been lessened, with the original phrase “the range of activity is mainly limited within the Chinese borders” being abolished and the scope of NPO income from public welfare activities that preferential taxation applies to has been expanded. These will facilitate the promotion of charitable donations in China and abroad.

4.3.3.2 Obstacles Hindering NPOs from Enjoying Preferential Taxation for Charitable Donations

(1)

Many public welfare charity organizations have difficulty in qualifying for tax exemptions or pre-tax deductions of their income from public welfare donations. Preferential taxation for public welfare donations has two meanings. One is preferential income taxation of public welfare donations received by NPOs and the other is pre-tax deduction of income tax payable for donors who make public welfare donations. These two preferential taxation policies are subject to, respectively, the prerequisite that a charity organization is qualified to have its income from public welfare donations exempted and that the organization is qualified for pre-tax deduction of the public welfare donations. Increasing the difficulty of obtaining these two special qualifications will not be conducive to improving the ability of charitable organizations to attract donations, which in turn will affect realizing tax deductions of the organization’s own income.

Regarding qualification for income tax exemption on their incomes, up to 2012, only 30% of China’s charity organizations have registered with the PRC Ministry of Civil Affairs and qualified for tax exemption of donation income. At the same time, the situation for qualifying for pre-tax deduction of public welfare donations is not positive. A majority of social organizations, particularly non-governmental and non-enterprise public welfare units, are excluded and not entitled to issue financial instruments to donors for their public welfare donations. Take Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, for example. In that city, where public welfare charities are relatively developed, only 53 social organizations are currently qualified for tax exemptions, accounting for less than 1% of the total and only 32 social organizations have qualified for pre-tax deduction of public welfare donations, accounting for only 0.6% of all social organization legal persons. Those that have qualified are basically limited to foundations and charity federations.Footnote40

Meanwhile, in China’s current tax system, when a donor makes public welfare donation via different charity organizations, they have to face different preferential taxation policies. In particular, the gap between governmental and non-governmental charity organizations’ capacity to attract donations through preferential tax policies is too large. The special full donation amount deduction only applies to donations given to charity organizations that are approved, founded, and recognized by the state, such as the Red Cross Society of China, China Aging Development Foundation, China Welfare Fund for the Handicapped, China Education Development Foundation, and China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation. Donations given directly to community charities or service organizations cannot obtain tax deduction certificates. This restricts the role played by non-governmental charity organizations in mobilizing social resources and adopting flexible forms of raising donations.

(2)

The non-profit nature of NPOs is not salient enough. Being a non-profit is an important precondition for a charity organization to enjoy preferential taxation of its donation income. At present, in the field of public welfare in China the distinction between profit-seeking and the non-profit agencies is not very clear. Fields other than medical and health services (such as education, science and technology, culture, sports, and social welfare), lack a clearly defined demarcation between non-profit and profit-seeking organizations and the relevant behaviors of these organizations, resulting in both non-profit and profit-seeking organizations sharing preferential tax treatment in spite of their differing behaviors.Footnote41 This confusion engenders the possibility of preferential taxation policies oriented towards charity organizations easily being illegally taken advantage. This is to the detriment of the public welfare role and social image of charity organizations, which will reduce the recognition of social forces and trust in the identity of charity organizations as serving the public interest. It will even depress the public’s enthusiasm to participate in social donations.

4.3.4 The Implementation and Improvement of Tax Incentives for Public Welfare Donations

The “Interim Procedures for the Use and Management of Bills of Donation to Public Welfare Undertakings” issued by PRC Ministry of Finance in 2011 is conducive to public welfare donations in China gradually operating in more standard ways. The third plenary session of the 18th Central Committee of CPC made it clear that “more efforts shall be made to improve the system of tax deductions and exemptions for charitable donations and support the charitable undertakings playing an active role in poverty alleviation.” At an October, 2014 executive meeting of the PRC State Council, Premier Li Keiqang, emphasized once again that “The policy of tax deduction and exemption for public welfare donations should be implemented well and improved, more measures encouraging charity should be introduced, and the development of charitable organizations with poverty alleviation functions should be prioritized.”Footnote42 This signal points again to preferential taxation policies which function as incentives to charitable donation. We suggest that the following two measures be adopted to ensure that the policies of tax deduction and exemption on donation income can be practiced effectively to solve existing problems in that area.

First, enlarging the scope of preferential taxation policies. The latest enterprise income tax law raises the proportion of tax deduction for public welfare donations, yet there is still room for increasing the individual income tax deduction for charitable donations. To elevate level of benefit made possible by those preferential taxation policies, all the links involved in the process should be considered. Firstly, support various types of charity organizations enjoying the qualification of tax exemption on their income from public welfare donations. Secondly, allow the charitable donation of an enterprise in excess of the quota to be rolled over to the next year for deduction, so as to encourage the enterprise to increase its donation volume as much as possible. Lastly, make sure that the formulated preferential taxation policies oriented towards public welfare donations apply to different donated contents and forms, and effective tax incentive measures oriented toward diversified donation forms should be introduced in timely fashion.

Second, improve the operationalization of qualification for tax exemptions. Civil affairs departments can join hands with finance and taxation departments in optimizing and implementing the process of qualifying all types of charity organizations for tax reduction and exemptions. They can also strengthen efforts to publicize the preferential taxation policies so that the charity organizations are well informed of the specific standards, requirements, and procedures for applying and handling applications. At the same time, the policy constraints on non-governmental charity organizations should be suitably relaxed and the blind spots and gaps in the existing preferential tax policies should be made up for or filled out, so as to put into effect to the greatest extent the preferential tax policies oriented toward public welfare charity organizations. Additionally, charity organizations’ capability of raising donations should be boosted correspondingly and their opportunities to receive donations should be increased so that the incentive of preferential tax policies for charitable donations can be functional and fulfill its purpose.

4.4 Internal and External Supervision Mechanisms

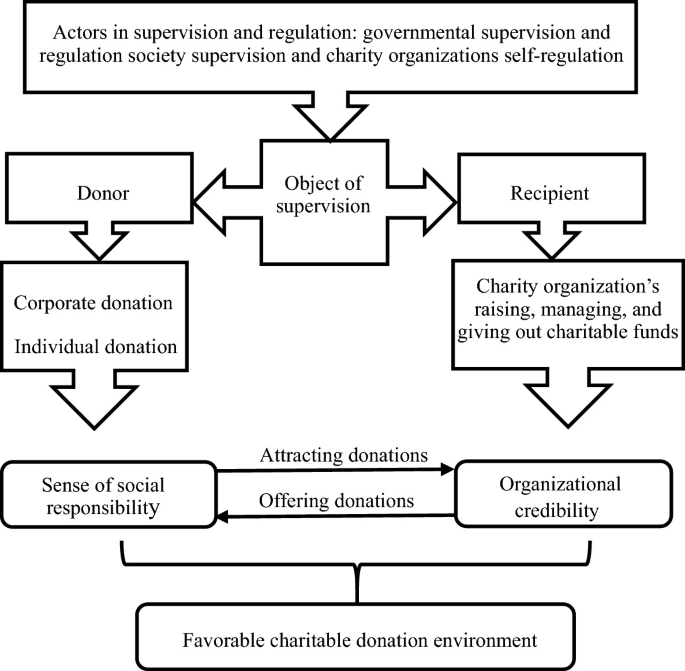

Usually, supervision and regulation involve governmental supervision and regulation, social supervision, and charity organization self-regulation. The supervision and regulation of the donors, recipients, and their behaviors are beneficial to boosting the transparency of donations, fortifying the credibility of charitable organizations, and guaranteeing that enterprises and individuals fulfill their social responsibility. Therefore, the supervision and regulation mechanism plays an important role in maintaining the environment for charitable donations (see Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.2

Mechanism of supervising and regulating philanthropy

Full size image

4.4.1 Governmental Supervision

The main means of supervision and regulation used by government agencies include formulating relevant laws and regulations, as well as supervising administrative enforcement of them. Generally, government departments practice supervision and regulation of charity donation activities by virtue of the authority of state laws and regulations and the coercive power of government.

4.4.1.1 Current System for Supervision and Its Performance

1.

Supervision by Laws and Regulations

China’s standards for managing enterprises’ participation in charitable donation and fulfillment of their social responsibility can be found in different laws, regulations, and documents, such as the “Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1999), “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Donation for Public Welfare Undertakings” (1999), and “Enterprises’ Accounting Standards” (2007), as well as the “Circular on Strengthening the Financial Management of Enterprises’ External Donation” and the “Circular on Issues of Strengthening the Financial Management of Central Enterprises’ External Donation,” issued by Ministry of Finance in 2003 and 2009 respectively. Specifically, the articles concerned involve the requirement for enterprises to adhere to principles of voluntariness and sincerity in their external donations, formulation and implementation of the internal procedures for managing external donations, supervision of external donations by enterprises auditing (or supervising) agencies or financial management departments, etc.Footnote43 The purpose of these is to prevent disordered donation behavior by enterprises and to ensure their proper fulfillment of social responsibility. The management of central SOEs external donations should abide by the relevant provisions in “Some Regulations on Incorruptible Employment of Leaders in State-Owned Enterprises,” which emphasizes that donations by SOEs must be approved by institutions that perform the duties of state-owned asset contributors.

For the supervision and regulation of individual donation behaviors, provisions in current laws and regulations clarify the responsibility for those ill-intentioned donation behaviors such as fraudulent donations, “promising but not donating,” and “donating less than promised.” Article 188 in China’s Contract Law stipulates expressly that “In the case of a gift contract the nature of which serves the public interests or fulfills a moral obligation, such as disaster relief, poverty relief, etc., or a gift contract which has been notarized, if the donor fails to deliver the gift property, the donee may require delivery.”Footnote44 At the same time, a gift contract the nature of which serves the public interests or fulfills a moral obligation, such as disaster relief, poverty relief, etc., or a gift contract which has been notarized, cannot be canceled. The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Donation for Public Welfare Undertakings” also provides definitely for legal liability the donor must fulfill according to his gift agreement. Current laws and regulations not only protect the donor’s rights and interests, such as the right to make free choices, but also require him to fulfill his obligation. The government’s supervision and regulation of charity organizations’ processes of raising and managing the public welfare funds are inseparable from the formulation and implementation of relevant laws and regulations. The existing “Law on Donation for Public Welfare Undertakings” and “Regulations on Foundation Administration” carry clear provisions for the specific proportion and orientation of the amount to be used in charitable donation property received by charity agencies, particularly emphasizing adherence to the purpose of the donor in using the property. Besides the provisions for direct supervision and regulation of the funds obtained by a charity organization, relevant laws and regulations also give the donor with the right to be informed on and to make suggestions regarding the donated property and protect the donor’s right to cancel and remove his donated property if it is used against the donation agreement between him and the charity organization. This is a way of conducting indirect supervision and regulation. Since 2011, there has appeared a new point to be supervised and regulated by the laws and regulations. Both the contents of laws and regulations issued by the state and legal documents issued by local governments have been emphatic in stipulating that charity organizations shall disclose relevant information to society. At present, the content of and responsibility for donation information disclosure are clearly stipulated in one law, four government regulations, four department regulations and normative documents and seven local regulations or normative documents in China.Footnote45

2.

Administrative Supervision and Regulation

The effect of laws and regulations must be ensured by effective administrative enforcement of them. According to the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Donation for Public Welfare Undertakings,” in special periods such as serious natural disasters, donated funds directly received by Ministry of Civil Affairs, as well as local governments and their civil affairs departments, should be brought under the purview of government supervision and regulation. Within the civil affairs system, administrative supervision and regulation of the donated property can be carried out mainly by such means as special examinations, as well as disciplinary and auditing inspections and supervision. Supervision and regulation over donated funds received and used by charity organizations should be implemented mainly through the public administration of the charity organizations.

In the past several decades, the supervision and regulation of non-governmental charity organizations in China have been effected with annual inspections by governmental departments responsible for their registration serving as the central link. In this process, a non-governmental charity organization first submits its annual work report to the superior department in charge of its administration in accordance with relevant laws, regulations, and policies. Then, the department makes an initial examination of the report and put forth its opinion on the basis of the information available. Ultimately, the department which administers the registration of the organization carries out a comprehensiveness of all aspects to determine whether the organization passes or fails. The administrative supervision and regulation of donated funds is conducted mainly in the form of auditing charitable funds. State agencies that specialize in auditing and auditing agencies approved and set up by governmental departments, as well as their specialized auditors, are responsible for carrying out special or routine auditing of the economic behavior of charity organizations during the process of raising, allotting, and using charitable funds. In recent years, administrative control of supervision and regulation of charity organizations has been lifted step by step under the backdrop of the reform of the administration system. Since 2004, the reform allowing for a direct registration system has relaxed the restrictions on the registration and administration of charity organizations. When mobilizing social donations, the civil affairs departments no longer designate which charity organizations receive donations. Since 2011, the Ministry of Civil Affairs has started to plan to categorize social organizations engaged in public welfare and charity undertakings as public welfare charity organizations. Their supervision and regulation will be carried out on a unified basis by the Ministry’s Charity Department. The main contents of charitable donation under supervision and regulation include whether charitable fundraising behavior is standard and whether the public is informed of charitable donations and relevant financial affairs. Objects under such supervision and regulation do not include charity organizations such as Red Cross Society of China that are exempt from registration.

4.4.1.2 Factors Promoting the Government Supervision and Regulation Mechanism

1.

The Government’s Increasing Attention to Developing Charity Undertakings

The Report of the Seventeenth Party Congress of the CPC positions philanthropy as an important supplement to the social security system covering urban and rural residents, with an understanding of the absolute necessity of philanthropy in constructing the society. The Report of the Eighteenth Party Congress of the CPC further proposes that reform of philanthropy should be deepened and emphasizes that tax deductions and exemptions on charitable donations should be improved, supporting them to play active role in poverty alleviation. The Ministry of Civil Affairs has set up a special group for leading and coordinating philanthropy and a bureau for coordinating philanthropy and has released annual reports on the charitable donation in China from 2007 to 2013. 2011 saw the founding of the China Charity and Donation Information Center, which, with the support from civil affairs departments, has issued annual reports on charity transparency in China that are based on its surveys and investigations from 2011 to 2013. In 2013, as indicated by a series of documents represented by the “Annual Report on Government Information Disclosure in 2012” issued by Ministry of Civil Affairs, the government is striving to examine a system of social organizations’ public welfare information disclosure that combines administrative supervision and regulation with social supervision.

2.

Gradual Improvement of Rules and Regulations for Philanthropy

Informed by the practices of charities at home and abroad, a rigorous system of legal norms must be established for developing philanthropy. Such a system is the fundamental guarantee ensuring their healthy growth and orderly operation. China’s legislation concerning charities has accomplished considerable progress, with seven laws and regulations introduced, including the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Donation for Public Welfare Undertakings” and the “Regulations on Foundation Administration.” As laws, regulations, and policies play an indispensable role in pushing ahead the development of charities, in the face of the fact that China has not formed a complete legal framework covering the entry to and exit from philanthropy, the evaluation, supervision and regulation of philanthropy, the delimitation and transfer of public welfare property rights, relevant financial investments, among others, the consideration of “Charity Law” (Draft) has been both on the agenda of legislation and under active discussion in China.

4.4.1.3 Troubles with Current Supervision and Solutions

Relative to social supervision and self-regulation, the government’s administrative supervision and regulation of philanthropy have stronger coercive force. However, the current administrative supervision and regulation, with its main form being annual inspection and assessment, still lack a complete system of laws, regulations and rules as a guarantee. It is difficult for government supervision to be exerted effectively. Additionally, there are still issues with the coverage, efficiency, and process of administrative supervision and regulation.

1.

Relevant Supervising Laws and Regulations Still to be Improved